Signs that the UK’s job market is slowing down have reaffirmed predictions that interest rates will be left unchanged again in November.

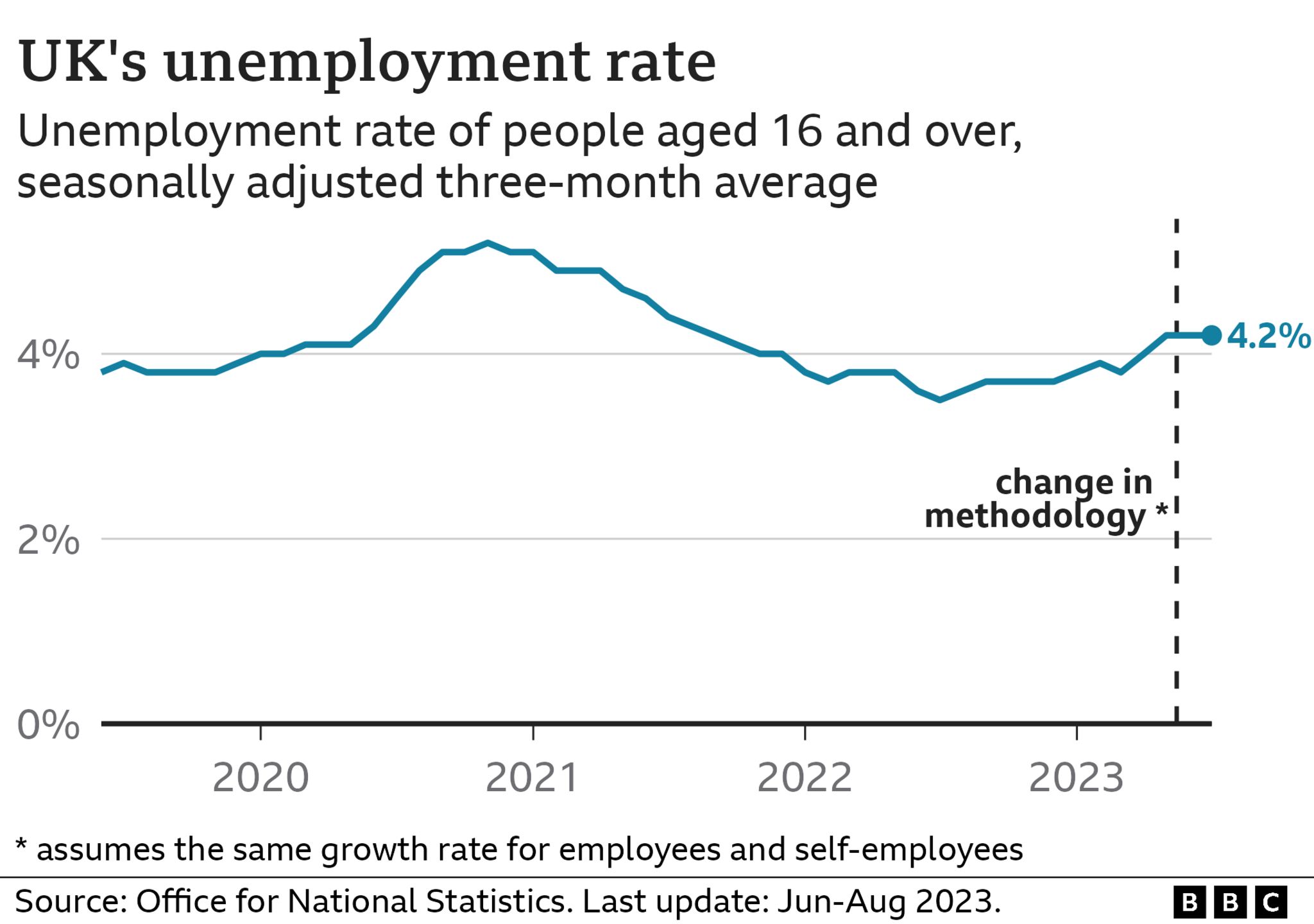

The unemployment rate was 4.2% between June and August, up from 4% in the March-to-May quarter, but unchanged from last month’s data.

Businesses appear to be hiring less as the impact of rising prices and higher interest rates starts to bite.

UK economic growth has also proved sluggish in recent months.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said August’s jobs figures had been calculated slightly differently than usual, in an attempt to make the data as reflective of the world of work as possible.

Balancing act

The Bank of England, which sets UK rates, will decide next week whether they should be increased, decreased, or kept on hold again at 5.25%.

The benchmark rate was left unchanged at its last meeting in September, ending a cycle of 14 consecutive rises. At the time the Bank’s governor, Andrew Bailey, said there were “increasing signs” that higher rates were starting to hurt the economy.

The Bank first started to raise rates in December 2021 in an attempt to control soaring consumer price rises.

But it is a balancing act – if rates go up too quickly, consumers and businesses may spend and invest less which tends to drag on the economy.

The impact of changes to interest rates, via higher debt repayments, also takes about a year to filter through to employers’ plans.

This month, one member of the Bank of England’s interest rate panel told the BBC that the bulk of the impact of the increase in interest rates was yet to hit the economy, adding younger and lower paid workers could be hit the hardest.

Official figures showed the UK returned to growth in August, following a sharp fall in July, however, economists have warned the economy was “only just grinding forward” and predicted that the Bank of England would opt to leave rates on hold again in November.

Ashley Webb, UK economist at forecaster Capital Economics, said Tuesday’s weak jobs numbers made that outcome even more likely.

“The Bank will probably continue to believe that interest rates are gradually doing their job and, in our view, it is unlikely to raise interest rates again,” he said.

Gabriella Dickens, senior UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said the figures “added to the evidence” that rates would be held, while Thomas Pugh, at consultancy RSM UK, said the Bank would probably wait “to see wage growth and inflation return to more normal levels, rather than resuming rate hikes”.

The UK is not currently in a recession but there have been concerns over weak growth, with the economy set to be a key battleground in the General Election, which is widely expected to be next year.

On Tuesday, a closely-watched economic survey indicated that output from private sector companies had fallen for a third consecutive month.

That prompted forecasters at Capital Economics to suggest “a mild recession is under way and that the Bank of England has finished hiking interest rates”.

Sarah Coles, head of personal finance at investment firm Hargreaves Lansdown, said there was “no clear overall shift in job losses just yet” but the UK needed to prepare “for more difficult times ahead”.

“This isn’t the agony of a collapsing jobs market: it’s the chronic malaise of an economy growing gradually weaker,” she said.

“With employment falling slightly, unemployment rising, economic inactivity up and vacancies dropping again, optimism is ebbing slowly away.”

The ONS estimated employment in the UK – which is the proportion of people in paid work – slightly decreased to 75.7% between June and August. It added that the economic inactivity rate, which measures people not actively looking for work, or available to start a job, had also edged up to 20.9%.

Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment & Employment Confederation, said unemployment remained low by historic standards and that the jobs market had been “normalising after the post-pandemic boom”.

“While vacancies are dropping, they remain above their levels of 2019,” he added. “But sector demand is varying widely and workers are facing having to make more transitions to new areas to find new roles. This transition is a primary driver of rising unemployment.”

Mel Stride, the Work and Pensions Secretary, said growing the economy was a “priority” and that the government was “bringing in the next generation of welfare reforms to drive down inactivity and help more people into work”.

He said there were now “more than one million more people on company payrolls compared to 2019, a near record high, and today’s statistics also show inactivity has fallen by over a quarter of a million since the pandemic peak”.

But Liz Kendall, Labour’s shadow work and pensions secretary, said the statistics confirmed “once again that the Tories’ dismal mismanagement of our economy is failing Britain”.