South Africa is gripped by a winter of discontent as the country faces its biggest ever power crisis.

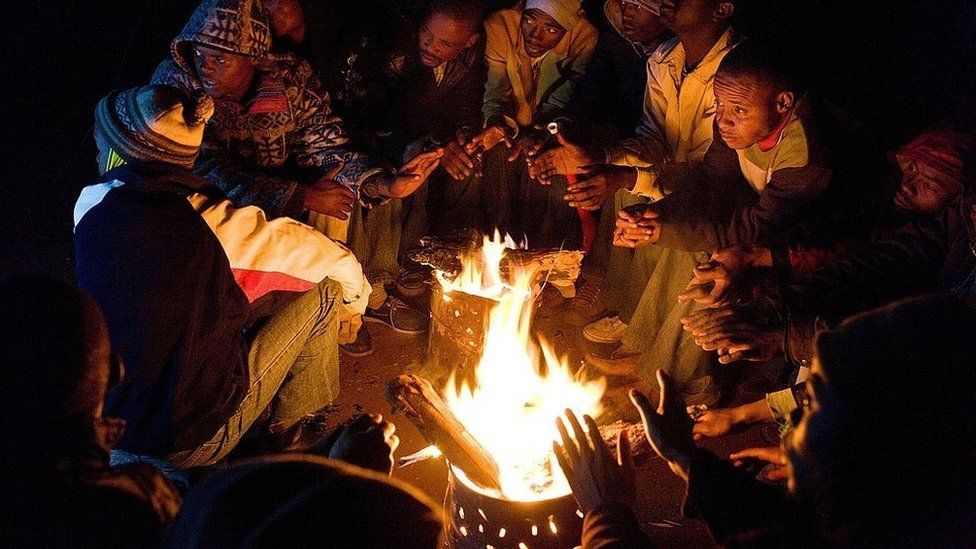

People are experiencing rolling blackouts of up to six hours a day and are having to face a bitterly cold winter with an erratic and unreliable power supply.

A typical day of what the state-run power company Eskom euphemistically calls “Stage six load shedding” consists of waking up to no power, driving to work through congested roads because the traffic lights aren’t working, being pummelled by the din of generators at the work place, and then finding power has been cut once more when you get back home.

It’s enough to make George Landon, a resident of South Africa’s main city Johannesburg, want to leave the country.

“I had a job interview in London. I’m booking my flight tomorrow because of the state we are in. Unfortunately I love my country, but the country needs to love us as well,” he says.

Poor management and corruption at Eskom mean South Africa has been experiencing power cuts for many years but this is poised to be the worst yet.

The country is fast approaching last year’s figure of 2,521 gigawatt hours of electricity cut from the grid. So far, Eskom has shed 2,276 gigawatt hours, and it’s only July.

To prevent a total grid collapse, Eskom cuts power to different parts of the country at a time.

Last week Eskom entered stage six for the first time since December 2019, meaning it had to cut 6,000 megawatt hours to prevent a nationwide blackout. There are eight stages of load shedding – each stage means 1,000 megawatt hours must be cut.

Many residents have to go up to six hours a day without power.

Eskom tells people when the lights will go off in their area, but it does not always adhere to its schedule. Sometimes, it may happen earlier or later.

The power cuts have been exacerbated by industrial action by Eskom workers who went on strike last week.

Wage negotiations between Eskom and workers from three unions broke down, prompting them to down tools, severely hampering operations and vital maintenance work.

Eskom boss Andre de Ruyter blasted the striking workers, calling the industrial action “illegal” and accusing them of holding the country “hostage”.

Eskom workers are classified as essential in South Africa and are not permitted to strike.

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) spokesperson Phakamile Hlubi, however, took umbrage, saying workers were “almost being pitted against the public” while the government was not acknowledging that its “major failures” had triggered the crisis.

A pay deal has now been reached but Eskom says that doesn’t mean an end to the power cuts as it will take time to clear the backlog of maintenance work.

Furthermore, Eskom is constrained by a massive $26bn (£22bn) debt, which is compounded by the fact that it has old, inefficient power stations that require constant work to keep them running.

Two new power stations that it has built have been beset by cost overruns, design flaws and ongoing delays. As a result, they are not generating enough electricity.

In May this year, Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe signed three deals to buy power from independent producers, seen as a step towards ending Eskom’s monopoly on power. They are considered the largest renewable solar and battery combined projects in the world.

While progress is being made in plugging the generating capacity shortfall, South Africans have been warned to expect load shedding for another two to three years.

The power cuts have had a severe affect on the economy and are likely to stifle economic growth and further deepen the unemployment crisis, which is a staggering 34.5%.

For Boitumelo Mokoena, who runs a small furniture manufacturing company in Alexandra, a bustling Johannesburg township, having no electricity is a death knell for her business, especially as it comes after the Covid lockdowns.

“When there’s no power the big machines must stop. It has affected our timelines. We’ve had instances where clients had deadlines and we could not deliver on time.

“Small businesses are already struggling in the market place, and if you don’t deliver it’s even worse,” Ms Mokoena says.

Small and medium businesses are the engine of South Africa’s ailing economy.

They comprise at least 98% of businesses in the country, and employ between 50% and 60% of South Africa’s workforce, according to a 2020 McKinsey & Company report.

“For every stage of load shedding there is about 250 million rand ($15.3m; £12.9m) lost on that particular day,” says energy expert Lungile Mashele.

“So you can imagine that on stage six, you’re basically looking at around 1.5bn rand ($92m) shaved from the economy.”

Johannesburg resident Tebogo Kolea can’t hide her frustration.

“I’m very angry because [household] budgeting for us is a problem right now. We can’t be paying for electricity and after every two hours there is load shedding again,” she says.