UK wages have risen at a record annual pace fuelling fears that inflation will stay high for longer.

Regular pay grew by 7.3% in the March to May period from a year earlier, official figures showed, equalling the highest growth rate last month.

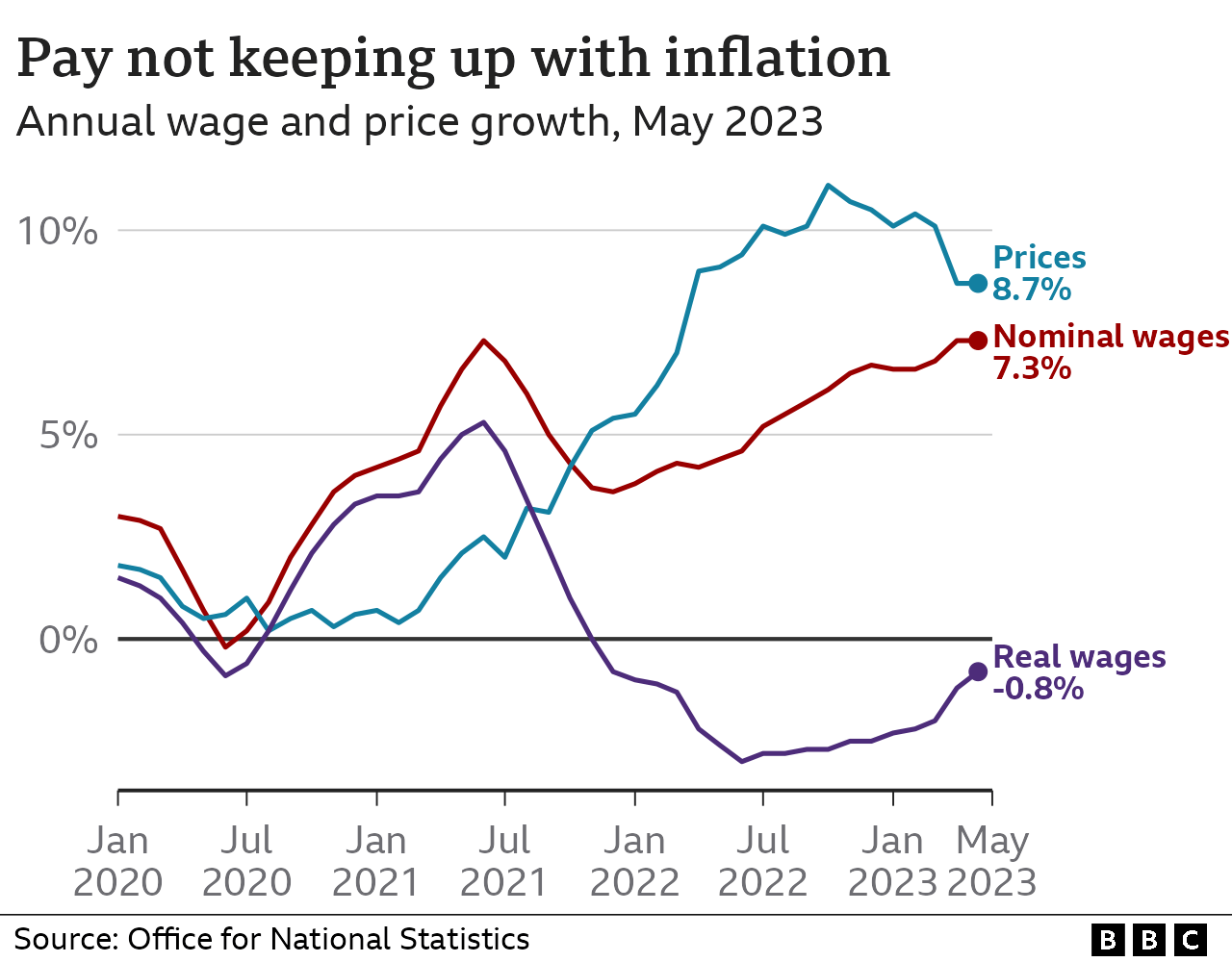

However, despite the record increase, pay rises still lag behind inflation – the rate at which prices go up.

The pace of wage rises has come under increasing focus by the Bank of England as it tries to control inflation.

The Bank has raised interest rates 13 times in a row in an attempt to reduce the rate of inflation, but it has remained stubbornly high.

It currently stands at 8.7%, well above the Bank’s target of 2%.

The concern is that strong wage growth will increase costs faced by companies and force them to push up prices for their goods even higher.

On Monday, the governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, said reducing inflation is “so important” as people “should trust that their hard-earned money maintains its value”.

While pay is growing at record rates, it is still not increasing fast enough to keep up with rising prices in the shops. Regular pay fell by 0.8% after the effect of inflation was taken into account.

The latest wage figures were higher than expected and Ashley Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics, said this “won’t ease the Bank of England’s inflation fears significantly”.

Last month, the Bank of England raised interest rates by more than expected, lifting its key rate to 5% from 4.5%.

Mr Webb said that while he expected the Bank to push rates to 5.25% at its next meeting in August, he added “we can’t rule out” an increase to 5.5%, saying “much will depend” on next week’s inflation figure.

Deutsche Bank said that an increase in rates to 5.5% next month “now looks more likely than not”.

Forecasts of more rate rises by the Bank have helped to push mortgage costs to their highest level for 15 years.

In January, when the UK’s inflation rate was above 10%, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak promised to halve it by the end of the year.

Mel Stride, the Work and Pensions Secretary, told the BBC’s Today programme that while forecasts still suggest that would happen, “it is not going to be easy”.

The figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) also showed:

- regular pay growth in the private sector was 7.7%, the highest rate outside of the pandemic period, while for the public sector it was 5.8%, the highest since late 2001

- the unemployment rate in the March to May period rose to 4%, up from 3.8% in the previous three months

- the employment rate also increased to 76%, which the ONS said was mainly due to more part-time employees

- job vacancies fell for the 12th consecutive time, dropping by 85,000 in the April to June period to 1,034,000.

There are indications that what is called “tightness” in the labour market – where there are too few workers to fit the jobs available – is starting to ease.

However, business groups have continued to stress the difficulty of finding the right workers, despite the slight rise in unemployment and fewer vacancies.

The government is now offering all workers a “Midlife MOT” on their careers to help those in their mid-40s and above to retrain.

The ONS data showed that pay rises were highest for those in better paid sectors such as finance, and were lower in retail.

The most up-to-date figures for just the month of May seem to show wage rises beginning to slow. This raises the possibility that pay increases have now peaked, which could lead to a calmer path for inflation.

Kitty Ussher, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, said that while wage costs remain “very acute” for companies there were some “hopeful signs” in the latest ONS figures, “with the number of vacancies falling and more people coming out of inactivity back into the labour market”.

The Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, said: “Our jobs market is strong with unemployment low by historical standards. But we still have around one million job vacancies, pushing up inflation even further.”

Labour’s shadow work and pensions secretary Jonathan Ashworth said the figures were “another dismal reflection of the Tories’ mismanagement of the economy”.

“Britain is the only G7 country with a lower employment rate than before the pandemic and real wages have fallen yet again,” he added.