Women on the minimum wage in Ghana have to spend one in every seven dollars they earn on sanitary pads, research by the BBC has found.

The BBC surveyed nine countries around Africa to see how affordable period products are. We compared the minimum wage to the local cost of the cheapest sanitary pads and found they were beyond the reach of many women.

While Ghana was the country with the least affordable menstrual products of those we surveyed, women across Africa are struggling with “period poverty” – something activists are trying to change.

Joyce, a 22-year-old Ghanaian, cannot afford to buy what she needs when she’s on her period.

“The only person available to help wants sex before he gives me the money. I have to do it because I need pads for the month,” she tells the BBC.

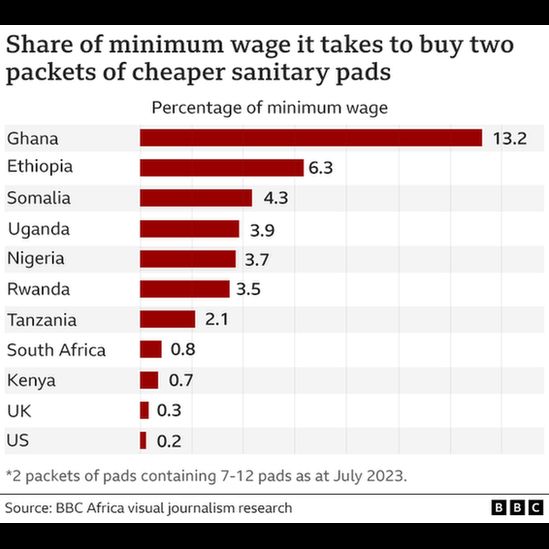

In six of the countries studied by the BBC, women on the minimum wage have to spend between 3-13% of their salary to buy two packets of sanitary towels containing eight pads – what many women will need each month.

As an assistant in a grocery store, Joyce lives with a family friend and survives on tips. Previously, she could afford to meet the cost of sanitary pads when it cost 4.88 Ghanaian cedis (45 US cents; 35 UK pence) per pack.

However, after the government increased taxes on sanitary products, a packet of pads now costs 20 cedis, pushing them out of her reach.

The price rises caused women to protest outside Ghana’s parliament in June 2023.

Joyce resorted to using toilet paper as makeshift pads, but when that proved unsustainable, she says she felt out of options and gave in to sexual demands in return for cash for pads. But Joyce’s struggle is just one among many.

The BBC used the minimum statutory wage in each of the nine countries studied, and the lowest priced pads available locally to calculate its findings.

Ghana was found to have the most expensive products relative to monthly income.

According to our research, a woman in Ghana earning a minimum wage of $26 a month would have to spend $3, or one in every $7 they make to buy two packets of sanitary towels containing eight pads.

That means for every 80 cedis they earn, they have to spend 11 cedis on pads alone.

By way of comparison, women in the US or UK would spend considerably less. For example, in the US minimum wage earners would spend $3 out of $1,200.

Francisca Sarpong Owusu, a researcher at the Center for Democratic Development (CDD) in Ghana, says many vulnerable girls and women are using cloth rags which they line with plastic sheets, cement paper bags and dried plantain stems when menstruating because they cannot afford disposable sanitary towels.

And the problem reaches far beyond Ghana. The impact globally is astounding.

According to the World Bank, 500 million women worldwide have no access to menstrual products.

They also lack adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management like clean water and toilets.

What’s tax got to do with it

Many menstrual health activists say removing “tampon taxes” is one way to help women inch closer to accessing and affording sanitary products.

Tampon tax refers to the different types of taxes imposed on feminine hygiene products, including period products such as pads, menstrual cups and may include sales tax, VAT and others.

Campaigners further say governments still look at feminine products as luxury items, rather than consumer goods or basic necessities, meaning the tax imposed on them is akin to a “luxury tax”, imposed on items considered non-essential, which only wealthy people will buy. These taxes are usually higher than on basic goods.

In 2004, Kenya became the first country in the world to remove tax on period products. In 2016 it went further to remove tax on raw materials used to manufacture sanitary pads.

Consequently the price of pads in Kenya has fallen, with the cheapest period products in 2023 retailing for 50 Kenya shillings (35 US cents; 27 UK pence), making it the country with the most affordable pads in our study.

However, women politicians and campaigners are pushing for further tax exemptions with the hope of lowering prices even further.

In South Africa, Nokuzola Ndwandwe, a menstrual hygiene activist, has been working to get VAT scrapped on period products since 2014. In April 2019, she managed a “monumental victory” when the government scrapped the 15% value added tax on sanitary pads and announced free sanitary towels in public schools.

Countries that do not tax sanitary towels and allow manufacturers to claim tax on the materials used (zero-rated) tend to have lower priced products overall.

But is tax exemption enough to ensure women and girls have access to pads?

In 2019 the Tanzanian government announced that it was re-introducing VAT on sanitary products, just one year after scrapping it. This was after consumer complaints that the prices had not fallen in the shops and markets.

Campaigners say prices didn’t fall because the tax was re-introduced before the supply chain of products had time to adjust.

Across Africa, and the world, lack of access to menstrual hygiene products due to high cost or because they’re not available in rural or remote areas has had a huge impact on millions of women.

While there is no single piece of research into how many girls miss school globally, studies in different regions and countries reveal that thousands of girls miss many days of education every year because they’re on their period.

A study in Kenya found that 95% of menstruating girls missed between one and three days a month while another 70% reported a negative impact on their grades, and more than 50% said they were falling behind in school because of menstruation.

Marakie Tesfaye is a founder of Jegnit Ethiopia, a movement for uplifting women and girls that has been pushing for tax exemptions and has been distributing reusable pad kits to girls in Ethiopia,

“We found data that showed girls in Ethiopia would miss as much as 100 days in a school year calendar, and when they missed school we noticed several things would happen,” she says.

“They would fall behind, repeat a class because they had no catch-up classes, drop out and get married or work as domestic workers, with little chance of ever advancing their education.”

Not just a women’s issue

Ibrahim Faleye was around 10 years old when he started buying menstrual pads for his sister. Growing up around girls in the Nigerian metropolis of Lagos, he thought it was a normal thing for every young man to do.

“We were an average family and we could afford sanitary pads so I believed it was the same for other families. When I found out that many people cannot afford the products, I was shocked,” he says.

Now aged 26, the public health practitioner has focused his work around menstrual health and education for girls and boys through his NGO, Pad Bank with the aims of stopping period poverty and helping boys learn to stop shaming girls.

“In Nigeria we have this culture where men are not allowed to talk about menstruation. We take the men through that process so they can understand and also care for women.”

South African campaigner Nokuzola lives with endometriosis, a disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside it and can make menstruation very painful. She would often find herself struggling at work.

“I was in a male-dominated team and I didn’t feel comfortable saying I felt sick. I felt ashamed and embarrassed and was worried about the repercussions on my opportunities,” she says.

“I thought about the millions of women going through the same thing. It was at that point that I felt it was time to deconstruct the narrative and end period stigma.”

So what does period justice look like?

UNFPA defines period poverty as “the struggle many low-income women and girls face while trying to afford menstrual products”.

The UN says overall menstrual hygiene means women and girls have access to clean water and soap, accessible and clean toilets and latrines and the power to access these facilities in privacy without stigma and shaming, coupled with menstrual education for both boys and girls.

In response to the BBC research, Nokuzola says: “It shouldn’t be this way. The fact that a woman has to choose between a loaf of bread, sustaining her family and menstrual products is really sad and concerning.

“This is a natural, biological process that comes every month so you have to neglect your autonomy over your body for the survival of your family. Menstrual products should be free.”

Nokuzola is now working to get a menstrual health rights bill passed in South Africa, so that period products can be recognised as a human right and women like Joyce do not have to resort to desperate measures in order to get them.

“We are suffering, I want to beg our government to remove the tax on pads. The truth is we are going through a lot just to menstruate. Why should I beg or starve myself just to menstruate? I think it is not fair at all,” says Joyce.